This article was originally published by MOTHERBOARD.

Last May, Iranians re-elected president Hassan Rouhani, a reformist leader, in hopes he will slowly edge Iran toward a more open and progressive sociopolitical culture.

In a country where 60 percent of the 80 million population is under 30 years old, the mobile-savvy, VPN-using youth in Iran have been resisting government control. Telegram, the encrypted messaging service, has become a popular form of communication for political expression, for example. But young people are also up against internet censorship, moral policing and fundamental religious clerics. Even with a relatively more liberal leader like Rouhani, Facebook and Twitter are still banned.

“Iranians are techy, they are ready.”

In their quest for expanded civil rights, some Iranians are taking ideas from Silicon Valley to the streets of Tehran and channeling them into apps that fill the gaps in health, education and dialogue. Built by Iranians both at home and abroad, there is hope that these mobile solutions could work where protests and advocacy has not.

“They want Iran to open up, it’s very clear,” said Firuzeh Mahmoudi, co-founder of United 4 Iran (U4I), a US-based non-profit that is working to advance civil liberties in Iran through technology. “Iranians are techy, they are ready.”

At the Oslo Freedom Forum (OFF), an annual human rights conference, Mahmoudi told me how technology in her country is being wielded as a tool for political dissent. Mahmoudi herself is an Iranian, though raised mostly in the US. She said the Iranian government now deems her an “anti-revolutionary fugitive” because of her work and political views.

But with around 20 million smartphone users, and a million new smartphones being added to the market every month in Iran, it’s clear she is not the only one looking to technology for change. The spate of new apps targeted toward Iranians and their rights reveal their priorities.

Avoiding the Moral Police

One app that sparked success upon its release was Gershad, which helps users protect themselves from the Gasht-e Ershad (guidance patrol), the so-called “morality police” of Iran. This de facto police force identifies and arrests anyone deemed to be inappropriately dressed, or in violation of Islamic cultural values, as reported by Iran Wire. Inevitably, women are more persecuted than men, as one of the main responsibilities of the morality police is to make sure women wear the hijab according to Islamic law.

The app is crowdsourced and takes information from its users, similar to the traffic app Waze. Gershad allows its users who see a checkpoint to indicate its location on the app’s map, allowing other users to find another route to avoid confrontation with the moral police.

The Gershad developers, who remain anonymous to protect the users and developers, explained on their website that the idea stemmed from the fact that many Iranians experience humiliation and disrespect from the Gasht-e Ershad. Angered by this “unreasonable injustice” they developed the app as a solution. “Why should we be humiliated for the most obvious right to choose the clothes that we wear?” their website asks.

The app was downloaded over 16,000 times within hours of its release, according to its creators. And though it was blocked very quickly by the government, tech-savvy users can still use it through VPN. Last year, the app won the Bobs 2016 Tech for Good award.

Tinder for Elections

Sandoogh96, which translates to Vote17 (2017 is 1396 in the Iranian calendar), is an app that was launched just before the elections last May. The app is inspired by the infamous dating app Tinder, which allows users to swipe right on another user if they’re interested, or swipe left if they’re not. But instead of swiping right or left for a date, Sandoogh96 users swipe to find out which politician is more in line with their ideas.

The app has different choices such as: “I want internet blocks to be removed” or “LGBT people should have the same rights as everyone.” The users political preferences then produce a list of candidates that align with his or her beliefs. One of the app’s best features is its “find a match” tool, which lets voters identify the candidates most aligned with their positions in six major categories including economics, culture, women’s rights, and foreign policy.

Sandoogh96 was developed through the Irancubator, a project created by U4I to develop civic technologies with community members. The app was created by IranWire, a media organization sharing news on Iran in English, and Small Media, a London-based research lab that specializes in projects supporting human rights in Iran.

A Period App With a Message

Another app made through Irancubator is HamDam, which translates to “companionship.” This is the first period-tracking app that allows individuals to use the Persian calendar.

HamDam includes the usual ovulation and period tracking features, but contains additional information about reproductive and legal rights for Iranian women. This is especially important because sexual education in Iran is very limited to young, straight couples getting married, according to the HamDam project lead Soudeh Rad.

Rad explained that sex education is also usually biased and centered around male pleasure, and that this app was meant to fill that gap. “Women’s sexuality is the subject of so much oppression around the world, which is connected to the struggle for the right to control our own bodies,” she said.

The app’s legal information is meant for women to protect themselves before marriage. Mahmoudi explained that in Iran, marriage license can act as a prenuptial agreement, and if the women don’t include language that gives both parties equal rights beforehand, the woman has very little rights in case of divorce. So, if the husband turns out to be abusive, a woman may be forced to choose between losing custody of her children or continuing to be a victim of abuse.

U4I told me the app has been downloaded more than 130,000 times, according to HamDam creators, and viewed over 1.5 million times.

Protecting Women from Sexual Violence

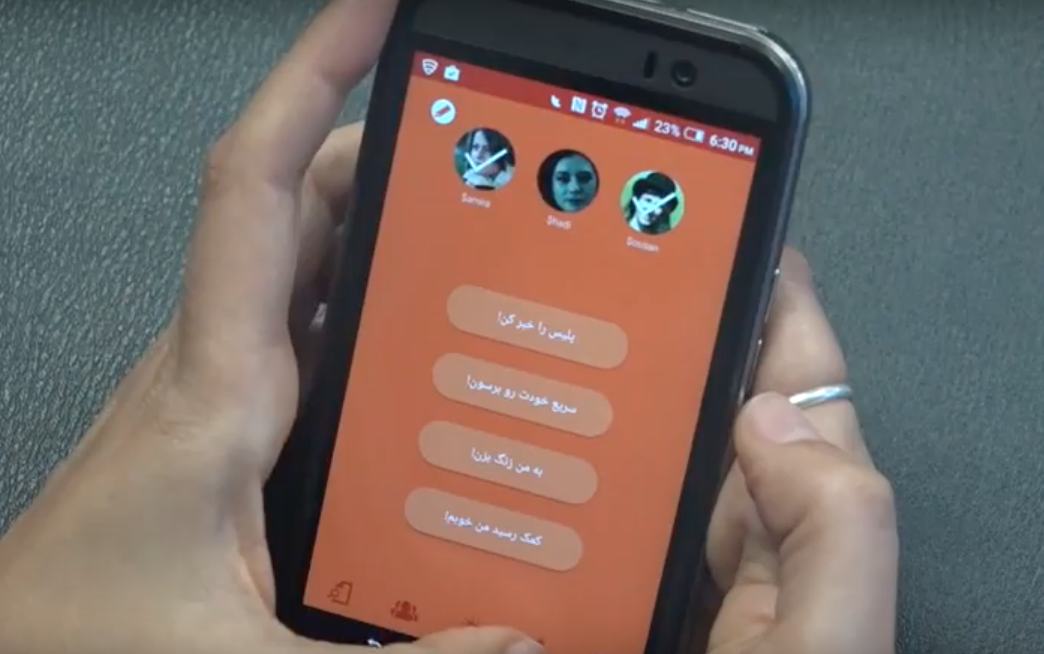

The Iranian app Toranj was inspired by app Circle of 6, an American app designed to protect college students from sexual violence. In this version, a woman can warn her trusted circle if she is in a dangerous situation. The circle will know the exact location of the user and has options to intervene, either with a phone call or by calling the police.

In Iran, approximately 63 percent of all women are subject to verbal, sexual, or psychological abuse, and most women do not report this to the authorities for reasons varying from guilt, or fear of economic hardship. But technology is trying to come to the rescue: Toranj mimics Circle of 6 to suit Iran’s context, and has information similar to that present in HamDam.

The app was developed in collaboration with Kurdish lawyer Shadi Shad, who has been working with victims of abuse. What made matters worse, she told me, was “the lack of social education and disregard for this type of behaviour that permeates within Iranian society—a self-inflicted ignorance which helps perpetuate a pattern of misplaced justification for abusive partners.”

A user, who is a doctor, sent a heartfelt letter to Toranj’s team describing her experience as an abused wife for 20 years. While she preferred to remain anonymous, her testimony serves as a proof that technology can be used to tackle social and human rights issues.

*

Many of the apps targeting young Iranians can’t be created inside the country because of the censorship and access issues that many young Iranians face. These civil liberties apps are developed by Iranians residing outside the country who cannot come back for security purposes. Technology in this case, is acting as a bridge, allowing their activism permeate people’s lives inside the country.