This article was originally published by Fast Company.

There are an estimated 40 million smartphone users in Iran. But ongoing government censorship, language barriers, and economic sanctions imposed on the country have made the app ecosystem that’s grown up elsewhere in the world unavailable to most Iranians.

“It’s almost impossible for Iranians to pay for any apps,” says Reza Ghazinouri, a program director at the Bay Area human rights organization United for Iran. “Iran’s economy is still isolated from the international economy.

And while isolation has at times been a boon to some Iranian and Iran-focused entrepreneurs—the country’s mostly cash-based economy has even spurred a cash-focused ride-hailing app—access to things like government and health information is still limited, partially due to censorship by the country’s authoritarian regime.

“There are hardly any apps that are civic-minded that are in Persian,” says United for Iran’s director, Firuzeh Mahmoudi.

To try to change that, the organization launched what it calls the IranCubator—an incubator that provides funding and support to developers building software to “advance civil society” in the country. It’s part of a wider push by developers and nonprofits around the world to create content deliberately aimed at populations underserved by the existing app ecosystem.

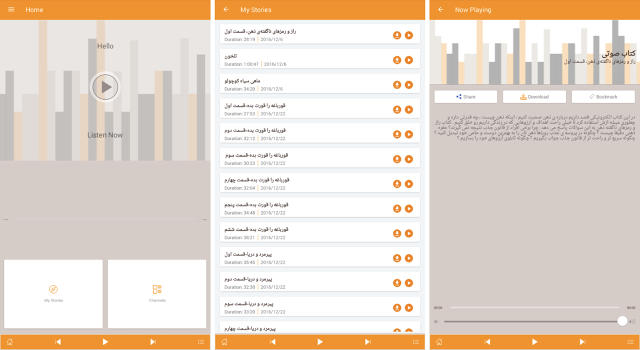

This month, the incubator released its first app—a podcast tool called RadiTo, with menus in Farsi, as well as underserved Iranian languages such as Balochi and Kurdish—and plans to deploy additional smartphone software in the coming months.

Like many podcast apps, RadiTo lets listeners download listening material through their home internet connections instead of through expensive mobile data connections. But the app features Iran-focused content from around the world, including some voices and positions that aren’t typically heard in the country, Mahmoudi says.

A series called Taboo, for instance, focuses on atypical-for-Iran topics from separatist movements to the female orgasm. Another podcast, called RadioGeek, discusses issues of technology and society from around the world. Still, the group does have some limits on the podcasts it will include, in line with Iranian sensibilities: Explicit language can be a no-no, and one suggestion that could promote sectarian conflict was rejected.

To limit censorship, recordings are encrypted and downloaded from public cloud servers used by other internet services, making the app difficult to block. With the Iranian internet routinely restricted, the country’s web users are no strangers to tools like encryption, proxy servers, and virtual private networks to get around pervasive censorship. In fact, the IranCubator team plans to promote RadiTo through ads on Psiphon, a circumvention tool developed by a Toronto-based company and widely used in Iran, says Ghazinouri.

Other organizations around the world are also focusing on making smartphone apps more useful at solving problems for new sets of users. In Saudi Arabia, a local foundation launched an app last year designed to help volunteers assist poor residents with health issues and information, and a Hong Kong businessman active in Africa recently sponsored a set of apps designed to help people in poorer countries diagnose and treat common eye conditions. And even internet giants like Google have begun making a serious effort to adapt their tools to the tastes and internet connection speeds of underserved parts of the world.

Mahmoudi says IranCubator’s efforts could also serve as a “pilot case” for building similar apps for other places in the world. And while the IranCubator developers aren’t physically on the ground in the country they serve, that can actually be an advantage, given the safety issues they might face in Iran.

“There’s a very specific niche that we can play that can’t be played inside the country,” she says. “We have capacity that doesn’t exist in the country, and we have security.”

IranCubator’s apps themselves are carefully audited by external testers for security, and the incubator is keeping quiet about its ties to some projects for safety reasons, he says.

“Some of them we have to be quiet about and don’t take credit for them, because the subject is a little bit sensitive, and we don’t want to be putting users at risk by associating users with a foreign-based nonprofit,” he says.

United for Iran is also reluctant to reveal too much detail about where it receives its funding, in order to protect donors and their families in Iran and to avoid suggestions of ties to groups controversial with the government in Iran. (Commentators have occasionally suggested the group may be linked to U.S. attempts to influence public opinion in the Middle East.) Mahmoudi says funding includes foundation and individual support, as well as employer donation matching from tech companies like Google. The group also receives support from the U.S.-backed Open Technology Fund, which also funds work on well-known secure digital communication tools like Signal and Tor.

Among the next public IranCubator apps to be released is a women-centric tool called Hamdam (Persian for companion), says Mahmoudi.

“It’s in Persian, and it’s an ovulation and menstruation calendar, which is the first app of its kind in Persian,” she says. But the app will also include information about other women’s issues, from sexual health and birth control to preserving women’s rights in marriage. Traditionally, women getting married in Iran forfeit many of their rights, but some of those can be preserved by putting particular legal language into a marriage contract, she says.

“It’s very much a contract that you sign—anyone can write in whatever they want,” says Mahmoudi, and some of that sample language will be included in the app.

Another app, built in conjunction with a human rights organization called Harana, will feature a database of lawyers across Iran and their specialties, she says.

“For example, if you are arrested for drug-related accusations in a city in the southern part of Iran, these are the lawyers you should go to,” she says. “If you are arrested in Tehran for political reasons, these are the lawyers you should go to.”

Users will also be able to report human rights violations, and Harana will work with its in-country sources to investigate claims, Mahmoudi says. In general, making sure government officials or others looking to sabotage the apps don’t spam databases with fake reports is part of the process of securing the apps.

United for Iran already maintains an online tool called the Iran Prison Atlas, cataloguing how the country treats its political prisoners, and the organization can often focus on providing information that just wouldn’t be possible inside Iran itself.

Once the initial versions of the apps are rolled out, Mahmoudi says, the project faces a problem that will be familiar to all app developers: keeping everything up to date. “As soon as the app is done, you have to work on version 2.0,” says Mahmoudi.